Amina Filali was a young Moroccan girl who was raped at the age of 15 then forced to marry her rapist. She was battered, bruised, and starved until she committed suicide in March 2012. She was 16 years old. Contributing to Amina’s suicide are her rapist turned husband, article 475 of the Moroccan penal code that absolves an aggressor of his crime once he consents to marrying his rape victim, the judge who called for a mediation instead of a prosecution against the offender, the police, and the religious clerics who have given their blessings to the rapist. Amina’s suicide exposes, once again, an entirely flawed legal system and deeply distorted patriarchal honor code that decriminalizes the oppressor and condemns the victim.

Behind her death is the lethal combination of state sanctioned gender violence, legal blindness, and societal silence.

Article 475 of the Moroccan Penal code states:

"Whoever, without violence, threats or fraud, abducts or attempts to remove or divert a minor under eighteen years, is punished by imprisonment of one to five years and a fine of 200 to 500 Dirhams. When a nubile minor is removed or diverted marries her captor, the latter may only be prosecuted when a complaint if filed by a person(s) entitled to apply for annulment of marriage and cannot be sentenced until after the annulment of marriage been pronounced."

According to the United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), Amina is a child. As a child under the age of 18, she is entitled to the three child-focused provisions in the CRC: protection, provision, and participation. The CRC explicitly includes the social and legal dimensions of protection as well as the provision of his/her adequate care. In a country where literacy (basic and legal) are still very low, one cannot expect the UNCRC to be common knowledge despite its recent inclusion in the civics curriculum of public schools. It would be legitimate, however, to expect the judge to fight for the “Best Interest of the Child” as the UNCRC stipulates. The judge who sentenced Amina to marriage should also have known that Morocco has ratified this UN convention much like it ratified the Convention to End All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). He should have remembered that Morocco’s constitution recognizes the primacy of international conventions over domestic legislation in matters of protection of women against violence. And he should have also honored the promises of gender justice made by the 2004 Family Status Code (mudawana) that allows Morocco to boast having one of only two progressive codes in the entire Middle East and North Africa. The 2004 revisions of the mudawana, despite its long, tortuous, and contested trajectory, has elevated the age of marriage of girls from 15 to 18 years.

Despite all these gender friendly moves, Article 475 remains alive, enforceable, and a looming threat that sentences young women to terrible lives, or worse, to premature deaths.

Amina’s suicide reopens a series of debates, questions, and concerns, only four of which I will discuss below.

First, the outpouring of outrage that Amina’s suicide has unleashed on the streets of Morocco, in cyberspace and beyond, reminds us about the intricate links between the wired and the wireless in this society, the online and offline community of protesters, and the younger and older forces of activism. Amina did not call herself an activist, nor did she expect to be viewed as one during her short life. As far as we know, she never accessed Facebook or Twitter, never owned an email account or a weblog, and probably never joined a street demonstration or signed a petition--not that she would have shunned any of these had she had an opportunity to learn how. Her suicide did, however, bring many voices together to express their anger and frustration at the incompatibility of archaic gender codes to women’s realities in the twenty-first century –assuming that the honor codes ever made sense.

Within the first few days of Amina’s suicide, human/women’s rights groups mobilized, and organized a sit-in in front of the local court that allowed the marriage to take place. Demonstrations and sit-ins in other cities around the country brought together the mothers/founders of the Moroccan women’s movements and the daughters of the movements. It united those who normally resent gender equality and those who fight for them, those who wear the label feminism as a badge of honor and those who shy away from it:

[On the far right side of the picture above, in brown shirt and glasses, stands Latifa Jbabdi, the co-founder and director of Union d’Action Feminine, one of the oldest secular feminist organizations in Morocco that has been militating against all forms of gender-based violence since 1987. Image from Magharebia.]

As thousands poured on the streets of urban centers and small towns, thousands of young men and women turned to social media to call for a protest march at the national level, circulated petitions to abrogate Article 475, and reached out to the broader inter/national public opinion for support and solidarity. Netizens immediately created a Facebook page to acknowledge the heroism of Amina, to document the protests, and raise awareness about the case. They have been uploading pictures, videos, posters, cartoons, and all information considered relevant to memorialize the tragedy.

[The above screenshot from the RIPAmina Facebook page reads “I killed myself because they did not protect me;” “raped at 15 and married to my rapist;” “No to rape with the complicity of the State.” Image from Global Voices.]

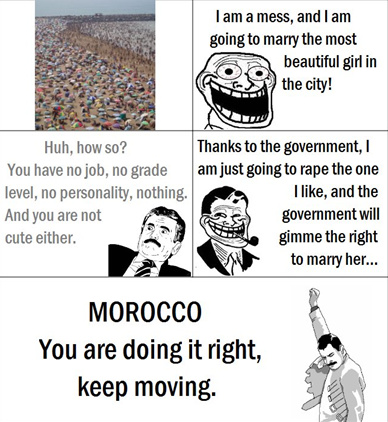

As images and posters point to the loophole in Moroccan law in various languages, Facebook activists called for a demonstration in front of the Moroccan Parliament for Saturday, 17 March 2012. Others turned to the sarcastic forumula of cartoons to capture the absurdity of the legal loophole:

[Cartoon expressing the absurdity of article 475. Image from RIPAmina Facebook Page.]

Moroccans in the diaspora also made their voices heard. A group of Moroccan women viving in the U.S. wrote “A Call for Justice” that stresses “No more criminalization of the victim and no more legal immunity to the criminal. We demand maximum punishment to the aggressor and complete protection and support for the victim.” The demands addressed to the Moroccan government make an unambiguous call to:

- Abolish Article 475 of the Penal Code.

- Abolish Article 20 of the Family Law.

- Pass the law for Combating Violence against Women.

- Undertake necessary legislative reforms regarding citizens and women’s rights that cohere with Article 19 of the constitution.

- Implement and respect the international conventions it has ratified, especially the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

- To bring to justice all those who condemned Amina to her suicide at the age of 16.

Thus, when Amina swallowed rat poison to end her life, she opened up yet another chapter of legal injustices and social hypocrisies against women. Her suicide forced Moroccan society to speak its own silences, face its own biases, and own up to its contradictions. This brings me to the second point I wish to discuss.

Secondly, it is precisely because of these silences that the suicide of Amina is linked to the self-immolation and subsequent death of Fadoua Laroui (February 2011). Fadoua’s death unveiled the specifically difficult conditions of single mothers in the country. To many, Fadoua is the Moroccan Bouazzizi. She is the first Arab woman known to have set herself on fire in protest against social conditions and injustices. As a single mother of two, her status in a conservative society as Morocco often translates as a prostitute. But while Fadoua could brave the stigma of single motherhood for years, she could not endure the injustice of being denied her right to social housing promised by the government. After many trips to her local town offices in order to reclaim the promised lot, she was faced with the reality that a) single mothers do not count as heads of households since they are expected to live with their parents, and b) her promised lot was traded for profit among business speculators. Just before she died, she was heard repeating: “Take a stand against injustice, corruption, and tyranny.”

Although Moroccan society is willing to claim Fadoua as “Our Mohammed Bouazzizi,” it has neither honored her death the way Tunisians did with their hero nor did it mobilize against her case en masse. True, women activists in Morocco did organize protest marches and dedicated 2011 Women’s Day to the memory of Fadoua Laroui. Moroccans for Change also dedicated the 100th Anniversary of Women’s Day to Fadoua, whom they placed among the “women at the forefront of blazing new trails, reaching new milestones, raising the bar on the fight for women’s plights and helping make the world a better place.”

However, with the exception of human rights groups, few cyber-activists, and netizens who honored her death, Fadoua did not receive wide media coverage nor did it grab inter/national attention sufficient enough to cause a stir around her, similar to Amina’s or Bouazzizi’s death.

I often ask people around me, my students and conference participants, to identify Fadoua and I always get surprised when a few actually do.

Here is a serious contradiction that Fadoua’s case brings up. Among the vexing cases of gender injustice that Moroccan society, as well as the international community are willing to deal with, some are considered more vexing or more urgent than others. Part of the explanation comes in the wise words of Aicha Chenna, founder of Solidarite Feminine, one of the very first organizations that acknowledged the tragic fate of single mothers. There are “no single mothers in Morocco” Aicha Chenna has been repeating for over three decades, “there are only abandoned mothers”- those who were seduced, promised marriage, exploited, raped, impregnated, and abandoned along with their children. Commenting on the case of young Selma, whose husband refused to both “register her marriage officially” after three years of “marital” life and declare his paternity when she got pregnant, she says: “A similar fate befalls many girls employed in domestic service, who have been made pregnant by the master of the house, then when the pregnancy begins to show, the family turns them out into the street.” These are some of the realities that Moroccan sociologist Soumaya Naamane Guessous exposes in her Grosse de la Honte (Pregnancy of Shame), also the title of her 2005 book.

Like Amina’s rapist and Selwa’s “husband,” the “father” of Fadoua’s children remained loose on the streets: he faced none of the stigma of practicing haram/illicit sex that Fadoua was stigmatized for, he lived through no dilemma of keeping babies or abandoning them on the street, he carried none of the burden of providing for the children in case the mother chose to keep her babies, and he faced none of the social persecution that followed her till her death. When Fadoua decided to set herself on fire, she opened up the debate about the silences in society that condemned her and single motherhood in general. The day she set herself on fire, she had completed the sixth complaint about her denial housing and had visited the local government office one final time, only to see herself dismissed in humiliation. Her decision to end her life highlights women’s inevitable and dramatic descent into despair when they live outside urban centers and beyond access to any legal services for the poor and the marginalized.

But if the support mechanisms remained elusive to Amina and Fadoua, and to many other young women like them, their fierce sense of justice and outrage pushed them to demand dignity by all means necessary.

Thirdly, it is about dignity. Dignity is a human right enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in the CEDAW, UNCRC and many other inter/national legal texts. The brave Tunisians who ousted former President Ben Ali, they did so because he was the enemy of dignity. They never called their revolution Jasmine, as many European journalists did. Instead, they called it the Dignity Revolution, or ثورة الكرامة (Thawrat al-Karāmah).

Those who rose up against various forms of oppression and injustice in the Arab world and well beyond it have been calling for justice and dignity. Legal scholars remind us about the historical evolution of the term and the multiplicity of meanings it has acquired over time, including dignity in socio-economic rights, freedom of speech, the rights of women, religion, and other rights.

Yet, the gender dimension of dignity has yet to be acknowledged and discussed. Dignity might be a universally recognized human right, but its denial is not experienced in the same way by all. Class, age, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, and other stratifying categories do matter here.

The death of Mohammed Bouazzizi, Amina, and Fadoua make different statements about humiliation –read denial of human dignity. The specific cases of the two young Moroccan women tell us that dignity is claimed for different reasons even when it is gendered and embedded in the same broader patriarchal definitions of honor and shame. Dignity is gendered in the way it is inscribed in women’s bodies, sexuality, mobility, and the practices of their everyday lives.

When young Egyptian women activists were forced to endure the virginity test in 9 March 2011, it was their dignity that was denied. When Samira Ibrahim pushed for a legal case against the army lawyer who carried out forced tests, she was seeking justice to restore the degrading treatment she received as a young woman. The acquittal of the lawyer in March 2012 proved that it is much easier to safeguard the reputation of a male state representative than to protect women against shameful violations of their bodies and honor. The experience of dignity is thus subjected to the logic of power relations that rule men and women’s lives and structure citizen’s relations with societal institutions and governing bodies.

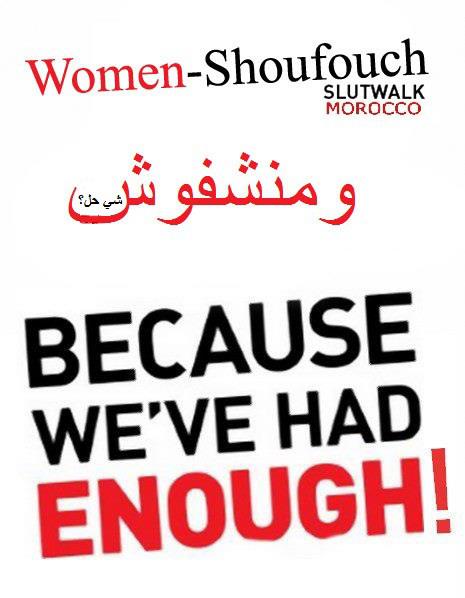

Egyptian scholar Khaled Fahmy is correct when he wrote in a recent article that the human body, and especially women’s, has been front and center in the revolutions, even though the leading slogan has been about Bread, Freedom, and Human Dignity. But women’s bodies have always been front and center in Arab societies. It has been confined, policed, regulated, (un)veiled, obsessed over, and harassed well before the revolutions. It is because it has been too front and center, regardless of what women feel or think, that many young Egyptian women spoke out loud in Kulena Laila (We are all Laila) and produced a harassment map -the same reasons that motivated young Moroccan women to scream “NO MORE” to sexual harassment. Shoufouch is a word all Moroccan women regretfully know far too well: it is the word that harasses them in every corner of the public space from men of all ages. Its meaning ranges from “what’s up?” “look here!” to more sexually loaded overtones of “shouldn’t we try?” The poster below subverts the meaning of this term by asking the question in Arabic “And, shouldn’t we be looking for a solution?” to end sexual harassment:

[Image from Women-Shoufouch Facebook Page.]

In the end, it is social inertia, legal discrimination, and cultural paralysis in the face of gender violence that made Fadoua and Amina use their own bodies to speak up about the pain of indignity. They both realized the legal system is too steeped in patriarchy and the social imaginary is too distorted by patriarchy to offer them much hope. This is why I stop at patriarchy as the fourth point I discuss. Patriarchy. Neo-Orientalism. Racism. What are the links?

In a recent appearance I made on Stream-Al Jazeera to discuss Amina Filali’s case, I was surprised at the ease with which Tweeters, Facebookers, and bloggers turned to Islam, as opposed to patriarchal appropriations of Islam, to explain Article 475 of the penal code. In fact, the word “patriarchy” was never brought up in the numerous comments and questions sent to the show. It has rarely, if ever, been used by the international media that has given great visibility to this case. Patriarchy has been both overlooked and undermined as a force shaping laws and attitudes towards this rape case. The erasure was simply disturbing. In parallel, I could not help but think about the killing of 17 year-old Trayvon Martin shot dead on February 26 by George Zimmerman, and the tension around using or not using racism to explain the killing. I am astonished at how much of an effort the community discriminated against –in this case the African-American – has had to put into persuading society that racism is still relevant and resilient -and how much it retains its full explanatory power. The picture below captures much of the veiling and unveiling processes that are going on in identifying the systems of oppression some fear to name:

[Image from twitpic.com]

Much like the term “racism” has had to fight its way through the rage caused by Trayvon’s killing, I found myself adopting a “professorial” (bordering on the pedantic) attitude to explain why patriarchy should be brought back to the discussion. Yet, while no religious references were brought up to explain the killing of Trayvon, Islam has been equated as a matter of course to one article of the penal code (475). In the process, this has erased the entire history of both patriarchal monopoly over religious texts (irrespective of religions) and an entire history of Muslim women’s struggles to exercise their right to ijtihad (critically reflect on and reformulate religious texts) and reclaim their rights under Muslim law. The equation of one religion (Islam) to the misogynistic 475 article of the penal code is as naïve as the condemnation of another religion (Christianity) for approving of the molestation of its children by some Catholic priests.

The simplistic coverage of Amina’s case by some international media outlets has resurrected the same old neo-orientalist script: “here goes again Islam, subjugating its own women; and, here is another case where the helpless victims need our rescue.” It is this much rehearsed script that I threw away in my discussion on Al Jazeera, much like many have done before me. Again and again, it puts many of us, Muslim women, activists, and scholars, in the awkward position where we have to simultaneously fight local systems of oppression that deny us our rights and stereotypical frames of misrepresentation that deny us our agency.

The deaths of Amina and Fadoua, as tragic as they are, make a powerful statement about their agency in choosing when and how to end their lives. They singlehandedly contributed to rewriting the neo-orientalist script that condemns Muslim women to frozen images of submissive, powerless, and pitiful victims of their religion. While international solidarity is a powerful and welcome approach to fostering gender justice around the world, one has to remain vigilant about what narratives get to be reproduced and which ones are brushed aside.

If Amina, Bouazzizi, Fadoua, and Selma died to regain their dignity while denouncing injustices in their societies, how can we deny that these injustices result from oppressive power relations and systemic forms of discrimination that sustain patriarchy, racism, neo-orientalism, or several other ugly isms? And if we concede that oppressive practices and laws are the product of human interpretations, an exercise in which one social group dominates the other, then we might have a basis to hope for more enlightened revisions in laws, so that justice and dignity can be enjoyed by all.